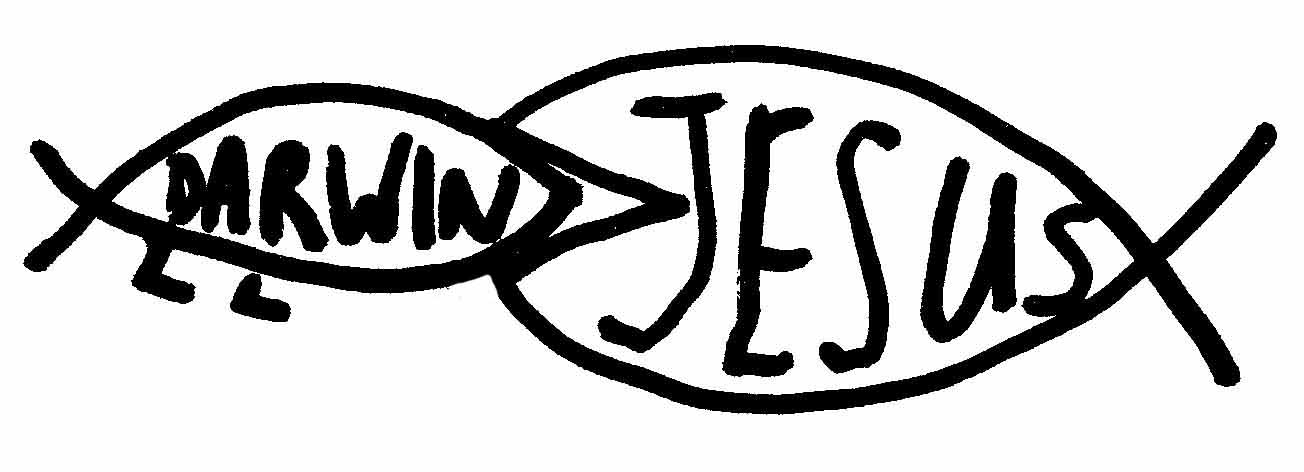

I am intrigued by the Jesus fish: you know, that stylized plastic fish found on the butt ends of so many American cars and trucks. A fish stands for Jesus because the acronym for Jesus Christ God’s Son Savior in Greek is the Greek word for fish, pronounced “ichthys,” root of “ichthyologist” (fish scientist) and “ichthyosauria” (an extinct order of fishlike predatory reptiles). The ichthys symbol or Christian fish was revived by evangelical Christians in the 1960s after many centuries of disuse and is now universally recognized:

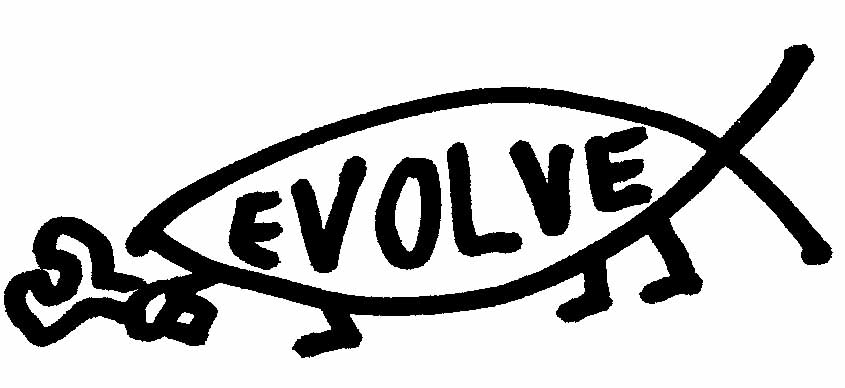

Fishlike, it has spawned a large school of offspring. I’m sure you’ve seen the wrench-wielding Darwin fish:

Perhaps you’ve also seen this rather aggressive reply:

There is also a Cthulhu fish and an idiotic Flying Spaghetti Monster fish, which I will spare you. The prize for Funniest in Show goes, in my opinion, to the following, which I am not making up:

There is also a Cthulhu fish and an idiotic Flying Spaghetti Monster fish, which I will spare you. The prize for Funniest in Show goes, in my opinion, to the following, which I am not making up:

The religious bumper wars also get fought out in plain old print, of course. COEXIST made out of diverse religious symbols; the earnest EVERY ABORTION STOPS A BEATING HEART; the sarcastic WHO WOULD JESUS BOMB?; and my all-time favorite, the exquisitely creepy GOD SAID IT, I BELIEVE IT, THAT SETTLES IT.

Why do we put Christian fish, Darwin fish, and other ideological signifiers on our cars? Because we know that random strangers must view them whether they like it or not. The public space between cars has the unusual and, alas, attractive property of being non-optional: comprehending any short text that intrudes on the visual field is involuntary, so reading a bumper sticker on the car ahead just happens. “No choice,” as Deckerd’s nasty boss grins in Bladerunner. Bumper stickers, including nontextual fish, are an inherently coercive act of communication, like standing up and lecturing on a bus. Billboards too. (Disclosure: I have a peace symbol located on the lower right rear bumper of my car.)

Some of the readers we draft are presumably friendly to our message, but I think mostly we are targeting those we think need convincing or at least pissing off. A Christian fish is a form of evangelization: a Darwin fish is a counter-taunt; a Christian fish eating a Darwin fish is a counter-counter-taunt; T. Rex noshing on an Ichthys is a deliberately whacky raspberry from the atheists’ bench.

As soon as I saw the dinosaur version, I realized with delight that it can be read as Tyrannosaurus Rex (King of the Tyrant Lizards) receiving a carnivorous communion. Here is a complete Christian theology of evolution in cartoon form. For Christians, Christ is the food of the world: we usually symbolize this by bread and wine, but the Ichthys is obviously edible too (and we roast lamb for Easter). Christ for dinner is as Christian as it gets. And if God entered the world in order that his sufferings might be like ours, as George MacDonald put it, and if we dare to read “our” suffering as that of all sentient beings, including our non-human ancestors and relatives, then are not all the sufferings of all the prey in history, including those torn to bits by T. Rex, represented on the Cross? Does not the “whole creation groan” (Romans 8:18–22)?

In this theology, Christ is the rent, broken, and eaten one, the lamb or the fish, the grape or the wheat, not in one place or one time only or in symbols or Sacraments only, but everywhere and always. But he is not only the eternal sufferer, the broken and eaten life. He is also the stalk or vine sprung from the seed’s tomb to become life and food, and he is the breaker and eater thereof. He is also the predator, and not only as a metaphor: fish are associated with Christ partly because he eats them (e.g., Luke 24:42-3). There are, I believe, only five specific items of food or drink that Jesus serves or ingests in the Gospels (not counting one failed attempt to pick figs): fish, water, wine, bread, and honeycomb. (Interestingly, the bee has, though relatively rarely, also been used as a Christ symbol.)

What a mighty menagerie is our Lord! — lion, dove, bee, and lamb; grape and grain; thunder lizard and hapless flounder.

I mean it. I don’t see anything silly about reading a T. Rex chomping its prey as receiving Communion. If “the young lions roar after their prey, and seek their meat from God” (Psalm 104:21), and if Communion is the type of all nourishment, of receiving our daily bread, even if the daily bread happens to be a fellow creature whose life we have ended, then T. Rex has every right to stomp and roar right down the aisle to the altar.

In the same general theological orbit I find thoughts like these:

Evolution has always been happening and is happening now. The crucifixion has always been happening and is happening now. The resurrection has always been happening and is happening now. Salvation history permeates reality, from Big Bang to Big Fade (or whatever the end is going to be). How could it not? Physically and literally, nothing exists apart from anything else. Every particle has a nonzero chance of appearing anywhere in space at any time. Quantum-entangled particle pairs grasping two ends of a single identity like kids about to snap a wishbone are flying all over the place, sharing ontology at infinite velocity (or something like it). The body itself is a flame or waterfall, a form or shape through which matter and energy flow constantly, not a static object. Oxygen atoms inhaled, utilized, and excreted by Christ, Hitler, and Groucho Marx reside within each of us right now. (The atmosphere is well-mixed over a relatively short timescale, and the candidate atoms number in the many trillions of trillions.) Touch anything and you have touched everything. To be “made man” is to be intimately involved with everything that ever was or will be. A purely local Incarnation is unimaginable because a purely local anything is unimaginable.

Christians who favor Jesus fish tend to be conservative, however, so it is a pretty good bet that next ichthys-sporting SUV you see will have a creationist at the helm. The ichthys symbol, so rich with evolutionary potential, is at public-relations war with Darwin on the highways of America. Irked by this tragic waste of theological opportunity, I have long toyed with the idea of crafting a hybrid: a Darwin fish and Christian fish kissing, with a little heart darting upward from the point of osculation. However, I see in Episcopal Life that a priest named Johnnie Ross not only beat me to the punch, but apparently — if I am reading the item correctly — got pulled over by a combination Baptist preacher and Kentucky traffic cop for his troubles: “The officer, a Baptist preacher, had seen the bumper art of the Christian fish kissing the Darwin amphibian on Ross’s car and demanded an explanation.” How’s that for highway fish wars? And I can’t help but wonder: did Ross violate some law of the road, or did the preacher-cop pull him over just because of the sticker? If the latter, wasn’t that a criminal misuse of police authority? At any rate, the ending is one I hope we can all live with:

“At 2:30 a.m., they were still talking.”

Thanks, Luke, for the kind words. You bring up good points, and your one caveat is sensible: I can see how in trying to strike a nice ringing blow on the anvil, I may have given a wrong impression. So, in answer:

I did not mean to put forward a “swirling world” of waterfall identities and non-absolute boundaries as more real than our everyday, commonsense experience of distinctness. That’s why I suggested that a “purely” local anything was unimaginable. Common sense is indispensable but it also blurs and fails when viewed under high magnification or in the light of certain facts that are usually backgrounded: and I think that our theology can be refreshed and enlivened by zapping it with these breakdowns. Seen in this playful or investigative spirit, the universal mutuality or interchange that permeates the physical world is a suggestive counterpart to Paul’s vision of our motley Christian crew as Christ’s “body,” and of the incarnation itself, and of the way both these ideas are acted out together in the materiality of the sacraments. Like, what’s all that materiality _about_? How far does it go, how deep does it run?

In my piece, I was leaning hard on universal flux and interpenetration: in response, you bring up the strain of intense _particularity_ that runs so sanely (and scandalously) through the New Testament. My notion is that here, as in so many things, the best picture is not one picture, but a superposition of pictures. Particularity is everything: this wounded hand and no other, this drink of water and no other, this unique person with a decision to make, this infinitely precious sparrow, these three trinitarian Persons who must not be “confounded” (Athanasian creed). But mutuality and co-identity are also everything: the trinitarian substance must not be “divided”, and we are all one body, and sacramental materials mixing with our saliva are, somehow, God — and so forth. We really need at least these two ways of seeing. Neither goes deeper than the other.

An exciting opportunity here, I think, is that so far, too few of us have tried dancing the scientific and evolutionary worldpicture around to the mood music of the old theologies, with their koan-like, mind-warping habit of superimposing intact incompatibles rather than mutilating either or both for the sake of a tidy fit. Although I’m strongly against drawing naïve one-to-one correspondences between bits of religion and bits of science, it really is striking how a century ago, something very like this superpositional style in Christian orthodoxy forced its way into modern physics (wave-particle duality, etc) — and stayed. No longer is it possible, without rank self-contradiction, to be scientifically literate _and_ to deride orthodox Christianity’s non-resolvable superpositions as inherently crack-brained . . . To neither confound nor divide, it turns out, is mandatory in science too, in the right places. It doesn’t prove a thing about God, but it’s suggestive.

— Larry

This is a great essay. I really enjoyed it, especially this insight:

"The public space between cars has the unusual and, alas, attractive property of being non-optional."

I do have one tangential hand-raise. Mr. Gilman states, "A purely local Incarnation is unimaginable because a purely local anything is unimaginable" and I wonder how much this is true. Admittedly, evolution is happening, salvation and resurrection are happening. We are exchanging millions and trillions of molecules, some of which may have been a part of Clinton or Lincoln or both.

But I have never woken up with Genghis Khan's foot or even his pinkie toe. I've never finished dinner with another thumb. Thus, the sort of swirling world that's envisioned by Mr. Gilman requires a move to abstraction that I find myself suspicious of.

It seems that the materiality of Christ is integral to the story. "Touch anything and you have touched everything," Gilman says. But that doesn't seem satisfying, somehow. It seems true that Thomas needed to put his hand through Christ side, put his fingers through his wrists. Touching an pear just doesn't seem the same.

So. Maybe the story of Priest Johnnie Ross and his bumper sticker is beautiful precisely because of its specificity. Perhaps what's so distasteful about the Jesus Fish / Darwin Fish bumper stickers is its manufactured ideology and the way we (normally) unconsciously digest it.

One last comment: I love Mr. Gilman's reading the image above as a "Tyrannosaurus Rex (King of the Tyrant Lizards) receiving a carnivorous communion", "a complete Christian theology of evolution in cartoon form". I was surprised. I didn't see a carnivorous communion. But I think it's right on. And I think it hones in on how messy these ideological wars are, how much transference there is between the battling parties.

That's it. Thanks for the article. Got me thinking.